Most websites use technologies that track website visitors. Take cookies, for example. A cookie is a small text file a web browser creates when someone visits a website. It often contains a unique identifier that helps websites and other online services recognize a visitor as they click from one webpage to the next. Cookies power shopping carts on e-commerce sites, allow visitors to remain logged in to their accounts for days or weeks, and store visitor preferences. These and other tracking technologies are also commonly used for analytics, marketing, and fraud detection.

These technologies, however, can also infringe on consumer privacy. To address this concern, many websites provide visitors with information about the tracking that takes place on the site and provide controls that allow visitors to manage that tracking. Privacy disclosures and controls are important tools for many consumers.

Cookie pop-up

Unfortunately, not all businesses have taken appropriate steps to ensure that their disclosures are accurate and that privacy controls work as described. An investigation by the Office of the New York State Attorney General (OAG) identified more than a dozen popular websites, together serving tens of millions of visitors each month, with privacy controls that were effectively broken. Visitors to these websites who attempted to disable tracking technologies would nevertheless continue to be tracked. The OAG also encountered websites with privacy controls and disclosures that were confusing and even potentially misleading.

We created this guide to help businesses avoid these pitfalls. Keep reading to learn about the mistakes we found businesses make when deploying tracking technologies, processes that businesses can use to help identify and prevent issues, and guidance for complying with New York law.

Different U.S. states, as well as other countries, take a variety of approaches to regulating tracking online. Depending on the jurisdiction, websites and other online services may be required to provide consumers with disclosures about tracking, allow consumers to opt out of certain kinds of tracking, or obtain consumers’ consent prior to tracking for certain purposes.

As of the publication of this guide, New York has yet to enact a comprehensive privacy law that specifically regulates when and how New York consumers can be tracked online. However, businesses’ privacy-related practices and statements are subject to New York’s consumer protection laws. These laws, which prohibit businesses from engaging in deceptive acts and practices, effectively require that websites’ representations concerning consumer privacy be truthful and not misleading. This means that statements about when and how website visitors are tracked should be accurate, and privacy controls should work as described.

Most websites track visitors through “tags” — snippets of code inserted into a webpage that direct a visitor’s browser to connect to a third-party service. The third party typically responds by sending a unique identifier that the browser saves in a cookie. When the browser later encounters a tag from the same third party on another webpage or site, the browser retrieves the cookie and sends the identifier back to the third party, allowing the third party to recognize the visitor.

Over a period of several months, OAG analyzed third-party tags and privacy controls on a variety of websites. The OAG found that 13 high-traffic websites – largely well-known e-commerce sites selling consumer products, such as apparel, books, and tickets to live events – had privacy controls that did not work as described. Together, these sites saw an estimated 75 million visitors in March 2024.

On these websites, certain marketing or advertising tags would remain active even after visitors tried to disable them using the sites’ privacy controls. As a result, visitors continued to be tracked after opting out of tracking. The OAG alerted the companies that operated these websites and asked them to investigate and fix the issues. All of the companies resolved the issues with their privacy controls.

Our investigation revealed that companies often make similar mistakes when deploying tags and other tracking technologies. Here are some of the key mistakes we found.

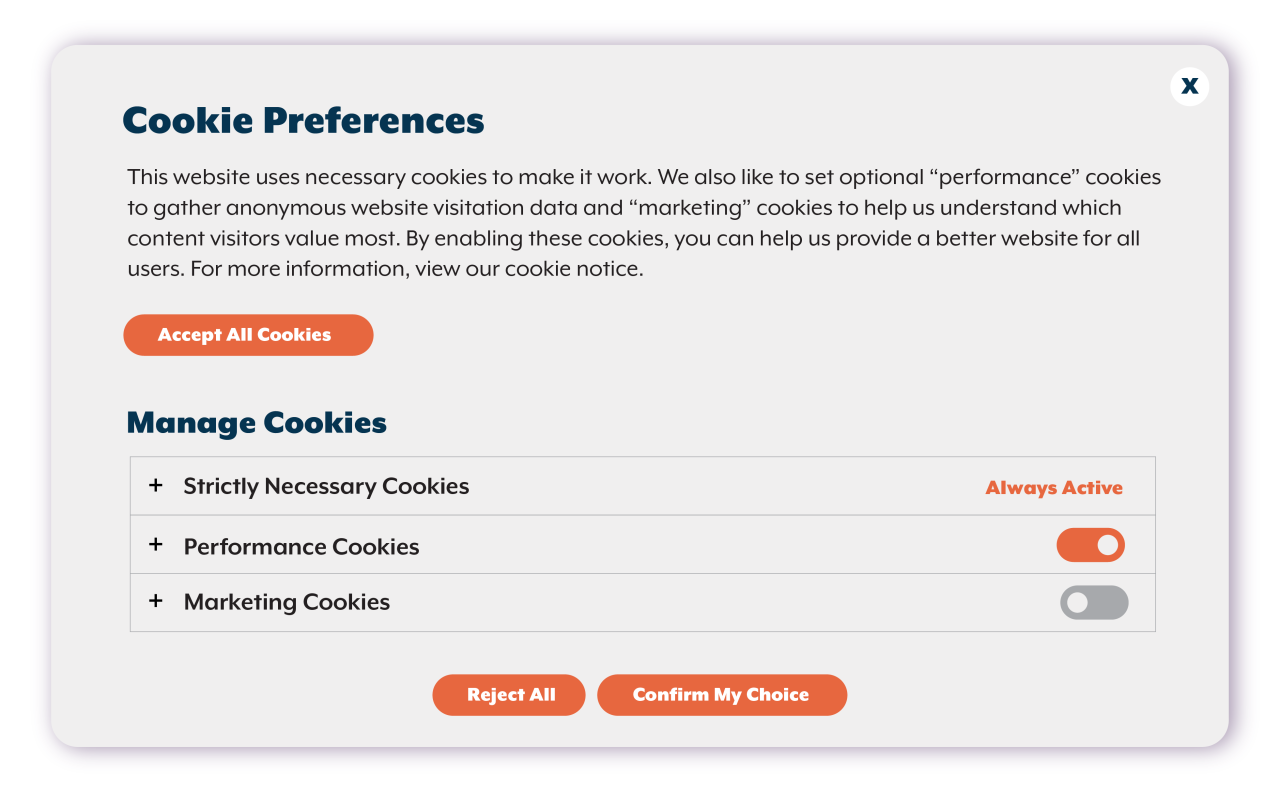

Most websites implement privacy controls using a type of software known as a consent-management tool. This tool typically allows categories of tags or cookies to be turned on and off. For example, tags used for marketing can be disabled, while tags used for fraud detection or analytics remain active.

Categories of cookies can be turned on and off

This functionality works only when tags are properly categorized in the consent-management tool. If a tag is miscategorized, or not categorized at all, it will not respond to the tool’s controls. This often means the tag remains active, regardless of a website visitor’s privacy selections.

We found that uncategorized tags were the leading cause of broken privacy controls: Seven of the 13 websites we identified had at least one tag that was not properly categorized.

In addition to consent-management tools, many businesses use a type of software known as a tag-management tool. As the name suggests, these tools are designed to simplify tag management. However, using both tag-management and consent-management tools on a single website can introduce technical and operational complexity. In most cases, each tool must be able to interface with the other and be properly configured to do so.

Our investigation found several websites where the consent-management tool was not properly passing opt-out signals to the tag-management tool. As a result, when website visitors then disabled marketing cookies using the sites’ privacy controls, the tag-management tools still allowed marketing tags to fire.

On some websites, several tags had never been configured to work with the sites’ privacy controls. The tags were instead hardcoded into the website. Because the tags were hardcoded, the consent-management tool was unable to control them and they would fire every time certain webpages loaded.

Several widely used tags offer settings that website operators can configure to limit how information collected by the tags is used. Meta, for example, offers an option called limited data use (LDU), which it says provides businesses with “more control over how [] data is used in Meta’s systems and better supports [] compliance efforts with various U.S. state privacy regulations.” Google offers a similar feature, restricted data processing (RDP), which it says can “limit how it uses data,” “to help customers and partners manage their compliance with the new U.S. state privacy laws.”

However, many of these features have been enabled only in states with comprehensive privacy laws that regulate online tracking, such as California, Connecticut, and Colorado. In other states, including New York, tag providers may not stop collecting and using visitors’ data when website operators have enabled these features. Several of the companies we contacted had mistakenly relied on these features to limit data collection when New Yorkers chose to opt out of marketing activity.

Before deploying a new tag, a business should understand what data the tag collects and how the data may be used or shared. Unfortunately, this information is not always readily available, because tag marketing materials and technical guides can be incomplete or unclear.

Although third-party cookies are the most commonly used tracking technology, they are not the only tracking technology that websites use. For example, one company we contacted passed information it collected about its website visitors directly to advertising companies, without third-party tags or cookies and outside the control of its consent-management tool.

Regardless of the tracking technologies they use, businesses must ensure that they do not mislead consumers about privacy and choice. Many privacy controls convey, expressly and by implication, that the privacy choices a visitor makes will be respected, regardless of the tracking technology the website uses. In these cases, businesses should ensure that visitors’ choices are applied across tracking technologies.

There are several straightforward processes businesses can use to help identify and prevent problems when deploying tracking technologies. The processes that are appropriate for your business may depend on the tracking technologies you use and how they are deployed. These processes can include the following:

Privacy controls and disclosures made available to New York consumers must comply with New York’s consumer protection laws. This means that the representations a business makes about tracking – whether express or implied – must be truthful and not misleading. Here are some key issues to look out for.

Websites with privacy controls typically convey a variety of information to visitors about how the site handles tracking and choice. These representations can be both express (found in statements in a cookie pop-up or privacy notice), and implied (conveyed by the presence and configuration of the privacy controls themselves). In most, if not all, cases, the website conveys that the privacy controls will honor a visitor’s selection.

Ensure that representations on your website about your privacy controls, whether express or implied, are accurate. This means privacy controls should work properly and as described.

The language used in cookie pop-ups often implies certain things. The wording on a button, for example, may create the impression that a visitor can turn tracking on or off. Your business should avoid language that creates a misleading impression of how your website handles tracking and choice.

One of the most common issues we encountered concerned cookie pop-ups that implied that visitors could opt in to tracking. For example, a pop-up with a button labeled “Accept Cookies” or “Accept All,” accompanied by text stating that clicking the button means “you agree” to the use of cookies, may convey to visitors that cookies will be used only if the button is clicked. This is misleading if cookies are in fact deployed without first obtaining visitors’ consent – for example, the moment that visitors reach the website.